Hazelius – the founders of the museum

In the late 19th century, amid the industrialization, an exhibition featuring scenes and objects from the disappearing rural culture opens in the heart of Stockholm. Behind the idea that would evolve into Nordiska museet are Artur and Sofi Hazelius. This is the story of their life project.

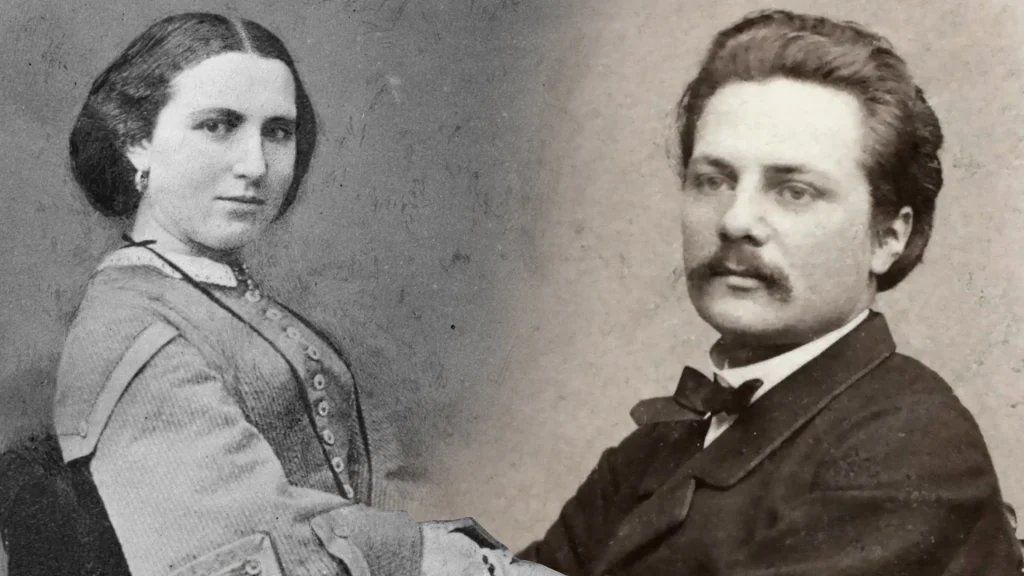

In 1864, a certain Artur Hazelius marries Sofi Grafström. The young couple resides at Kammakargatan 37 in Stockholm. He is a lecturer in Swedish at Nya Elementarskolan, and she, hailing from a cultured clergy home in Umeå, is linguistically, artistically, and musically talented.

Shaped by their contemporary society, they feel a strong urge to preserve the old for the future. Following a journey in Dalarna in 1872, they embark on a gigantic collection project of objects. Artur completes their joint project on his own when a tragedy befalls the family along the way.

The Hazelius couple

Artur Hazelius (1833–1901) is born in Stockholm in 1833. After completing his university studies, he focuses on Nordic languages and defends his thesis in Uppsala in 1860. He is actively involved in the ideas of the Scandinavianist student movement, which aimed to bring the Nordic peoples closer together, emphasizing the strong historical and cultural ties between the countries. Artur’s commitment gains him a vast Nordic network.

For ten years, Artur Hazelius works as a teacher in Swedish and Swedish literature at Nya Elementarskolan and Högre allmänna lärarinneseminariet in Stockholm. However, it is challenging to make ends meet, especially after Artur resigns from his teaching position in 1868 to work as a freelance writer.

Sofi Hazelius, born Grafström in 1839, is a highly gifted woman, as evidenced by the drawings and paintings she left behind. For several years, Artur and Sofi take in boarders and undertake translation work to supplement their income. Sofi translates from English to Swedish, among other languages.

A Life-Changing Journey

In the summer of 1872, the couple embarks on a journey to Dalarna. Throughout the trip, they witness how folk life, clothing, customs, and traditions are being replaced by new fashions and practices. They are seized by a strong sense that the old ways are disappearing and must be preserved for the future. It is during this time and place that the idea to establish a museum is born.

During the journey, they acquire what will become the collection’s first item, inventory number 1, a home-woven wool skirt from Stora Tuna parish. Sofi keeps a diary and is a quick and astute observer, adept at vividly expressing herself in writing. It is also during the journey that she makes recordings of songs and melodies.

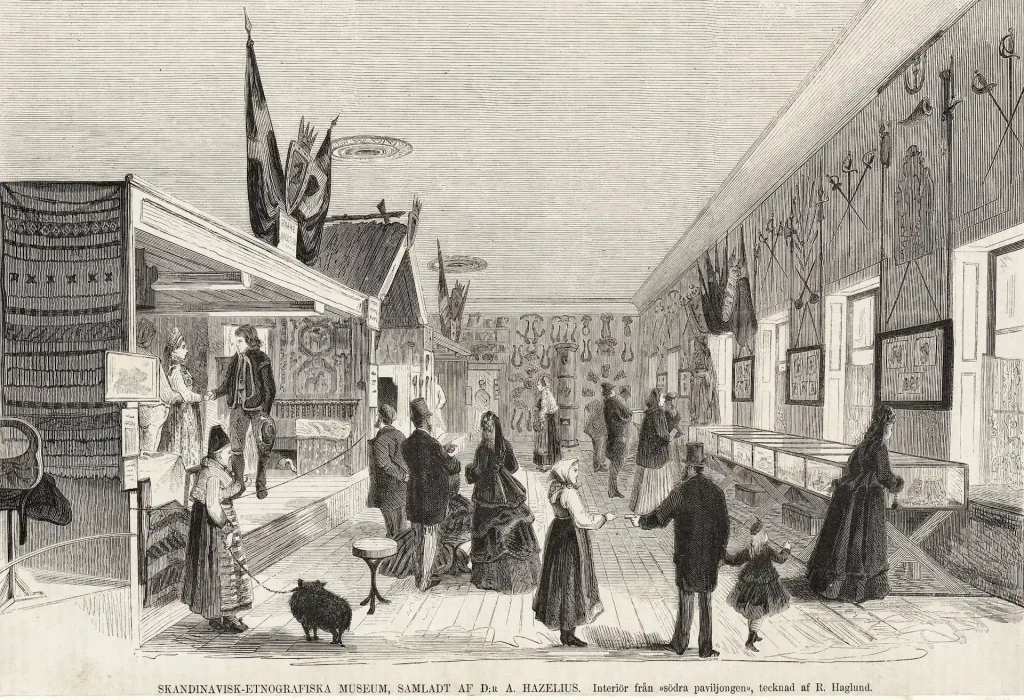

The Scandinavian-Ethnographic Collection opens in 1873

In December 1872, Artur formulates guidelines for the collection of objects for a museum. Having no personal fortune to finance his endeavors, he had to rely on people’s generosity and philanthropy.

He becomes a skilled and persistent collector (sometimes referred to as ‘Sweden’s greatest beggar’), with many contributing by donating objects or providing financial support. Hazelius referred to his helpers as ‘skaffare’ (gatherers). They acted as agents for the museum, and through their assistance, a large number of objects were purchased or donated. Sofi Hazelius participated in the museum’s early years of work.

[…] the museum's sole assistant. She faithfully shared the work, worries, and successes. […] Sofi Hazelius was a woman abundantly equipped in both mind and heart.

Artur about Sofi Hazelius

The collection work could entail some sacrifices. This is stated in the museum’s annual report for 1901:

‘During the early years, when the museum was still housed in Hazelius and his young wife’s home, where bonnets, bridal chests, and various tools began to accumulate, the rather limited household funds often had to be used to purchase some rarity. The intended new coat or winter coat had to remain undone so that the collections could be enriched with some artifact of rural art.’

Nevertheless, Hazelius affords to rent a space at Drottninggatan 71A in the so-called Davidsson’s pavilions. On October 24 1873, the Scandinavian-Ethnographic Collection opens its first exhibition. The realistic scenes with dolls and objects depicting events from rural life captivate the audience. Here, the focus is not on kings and wars but on the people themselves.

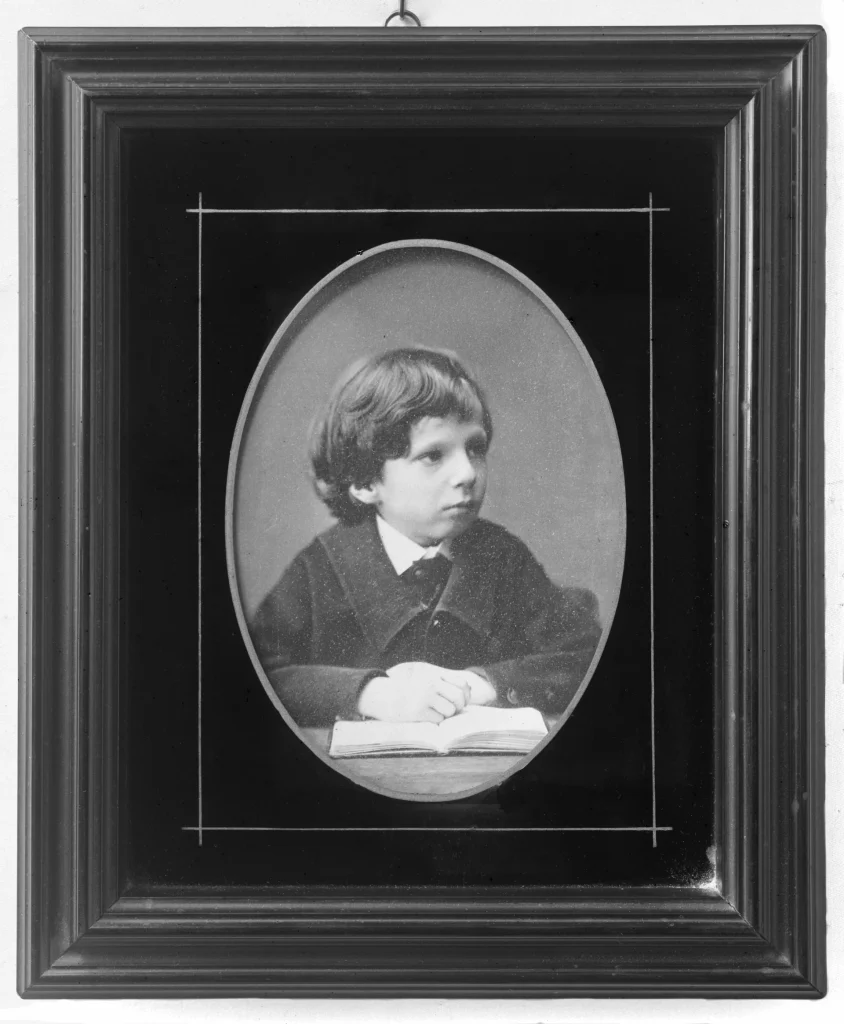

During this time, the couple awaits their first child. Gunnar is born in March 1874. It is a difficult delivery, and Sofi falls ill with puerperal fever. A few days later, she passes away only 34 years old.

Artur is now a widower and hires a nurse for little Gunnar. Despite his grief, he continues his and Sofi’s shared life project.

The collection becomes Nordiska museet in 1880

The Scandinavian-Ethnographic Collection continues to grow with the help of gatherers. In 1880, Artur reorganizes the museum into a foundation and changes its name to Nordiska museet. In the statutes, he writes: ‘It shall be a home for memories primarily from Swedish folk life, but also from other peoples related to the Swedish.’

During Hazelius’s time, a large number of objects are collected from the Nordic countries, especially from Norway, which was in union with Sweden until 1905.

It shall be a home for memories primarily from Swedish folk life, but also from other peoples related to the Swedish.

Artur Hazelius in the Statutes of Nordiska museet

Hazelius was not without critics. Some argued that he collected far too much, including items that were not always in the best condition; some even used the word ‘rags’ to describe parts of the collection. Others believed that he had too close and favorable a relationship with the press, leading to his museum receiving overly positive publicity and uncritical attention.

The visions become reality on Djurgården

The collection outgrows the space on Drottninggatan. Now, the vision is a palace-like museum on Djurgården. In 1888, the first sod is turned for Nordiska museet designed by architect Isak Gustaf Clason.

During the construction years, Artur also establishes his second dream – an open-air museum. Skansen is to showcase a miniature Sweden and opens to the public in 1891. Artur and Gunnar move to Skansen in 1892. They lead a rather solitary life, and Artur dedicates all his energy to museum work.

As Artur becomes increasingly ill, he passes away after a morning walk in May 1901, at the age of 67, in his home. A magnificent funeral procession carries him through Stockholm to his final resting place at Skansen. Gunnar succeeds him as the director of Skansen but passes away in 1905. In June 1907, the first visitors step into Nordiska museet on Djurgården. The palace for the people’s memories is a reality.

I wanted the collections to be presented in such a way that a visit to the future palace would evoke a strong and powerful atmosphere.

Artur Hazelius